I was born in 1950, two years after my family immigrated to the United States. By chance they put down in the small uphill Vermont community of Woodstock. It was a big move for them – from a dense, largely Christian society at the American University of Beirut to a small Yankee rural town in the northern hills of New England.

As a fourth-grader I was sent to the North Country School in Lake Placid where many of the teachers were artists and encouraged creativity in their students. That hit a note with me. By the time I was sixteen I had learned a lot about photography, or at least learned a strong connection with it. But I always felt like I had salt under my skin. I think I appeared “normal” in the sense that I spoke unaccented English and was quite light-skinned but I had little of the cultural and social presets that come from growing up with parents who go to picnics, play ball or skate or even hike up a mountain. I started skiing and did pretty well in competition, but my parents only showed limited interest in sports. My father, after all, had passed his college swimming test with a rope tied around his middle and his classmates skimming him across the water for the requisite distance; it wasn’t like physical prowess was big at home.

My parents were keen on schooling. I wanted to head straight into photography, but they thought that a liberal arts education had merit. They were right.

Dartmouth College was a great match for me. This was during the period of the Vietnam War and there was a vibrancy on campus that was hard to contain. Students and faculty were examining traditional roles and talking about things that don’t often get discussed.

It was my second year in college that a young faculty member in the Art History department invited the equally young photo-historian (Peter Bunnell) to teach a survey course about photography and he brought with him a slide collection from MOMA that was to die for and showed me the breadth of a world I hardly new existed in photography! After that I transferred for a credited year of graduate study with Minor White at MIT. So even though I completed a “liberal arts” degree (and took advantage of it) people always saw me with a camera.

After graduating I did creative projects, and sold prints to collections and individuals. But it wasn’t easy – these were generally bad economic times and I had little business experience. I did learn how to make hand-bound archival museum cases and constructed small production runs of these for others. My parents had been right to push me towards a profession that would be easier to make a living at, but photography was in my blood and getting out really wasn’t an option.

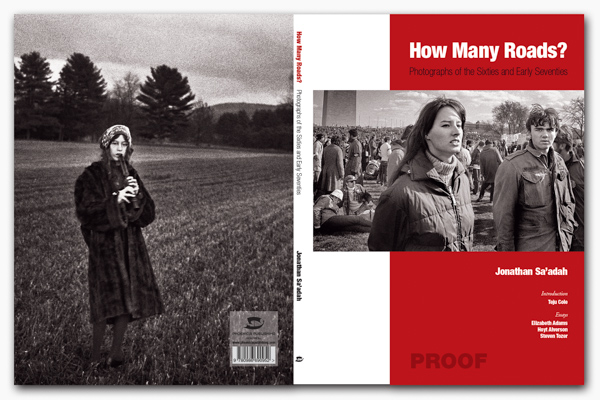

Many pictures in the book How Many Roads came from rolls of film developed without a darkroom, using gravity-fed spring water heated on a wood stove in a remote cabin.

Things started to improve on the reality-of-living front, however, when I received a Reynolds Fellowship in 1975. With that support I spent a year in Paris documenting the filming of Joseph Losey’s M. Klein. It was in Paris where I first felt the camaraderie of working with other people (Losey, the production company, and the film crew). On returning to the United States, I began looking for larger assignments working as a freelancer but with groups of people. In 1981, I married Elizabeth Adams and soon after we started a professional partnership. We combined the skills of graphic design and photography to form a communications partnership that continues today.

My main interests as a photographer have been portraiture, street photography, and pictures of social change. The photographs reproduced in How Many Roads are early examples.

A lot of my work in recent years has involved imaging through different devices – it used to be darkroom work. And photography itself has changed too – changed enormously. What we now call a camera and the things you can do with it have expanded so enormously. And photography, instead of becoming less important, is now almost constantly with us. It’s a big change from when photographs were relegated to pieces of paper.

This blog and website are a place to show work, to talk about topics of interest, and also to hear from you and to stay in touch. Please sign up for the mailing list and don’t be shy about commenting. Thanks for visiting.

Jonathan Sa’adah

contact information

All photography and writing on this website © 2017 Jonathan Sa’adah – no use without written permission.

Recent Comments